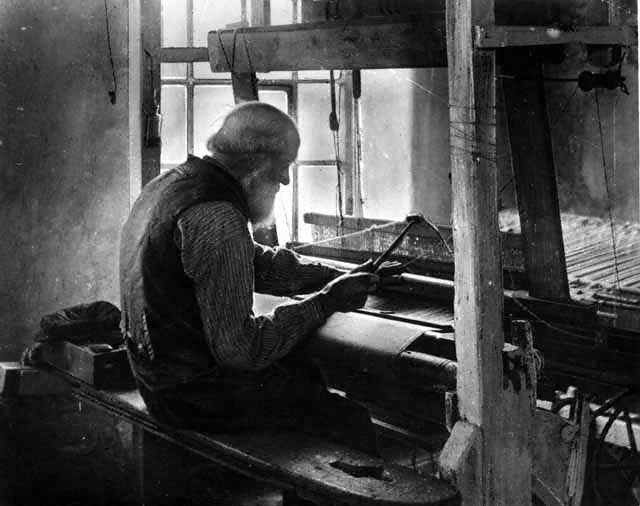

On the 1861 census, a young woman called Jane Bennett is recorded as the head of a household, living in a house on The Rank along with two other ‘households’. At first glance, it’s very easy to miss the only other person who lives with her (and I missed it, the first time I looked at the scan), because his name is written in different ink, in tiny letters below Jane’s name.

He is Fred Bennett, aged nine months old, the son of Jane, who is 17 years old and unmarried.

| Name and Surname of each Person | Relation to Head of Family | Condition | Age | Rank, Profession, or Occupation | Where Born |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jane Bennett | Head | Unmarried | 17 | Wool Hand Loom Weaver | Wilts, North Bradley |

| Fred Bennett | Son | 9 months | Wilts, North Bradley |

Why was his name added in later, almost as if he was an afterthought? And why was Jane living separately from her family, a few doors away? Perhaps there’s a bigger story here, maybe a of a young woman who had been turned out of her family home, into a house full of people she wasn’t related to. Did she try to hide her baby son, who, at some point, came to the attention of the enumerator and was recorded later after the list had been filled in? Or maybe she simply preferred to raise her child alone, away from her boisterous younger brothers, yet still within reach of the support of her parents, and the enumerator was rushing the job! We can’t know for certain, and drawing any firm conclusions would be impossible. But later records give us more interesting clues.

Ten years later, Jane is still on The Rank, now married to Henry Webb.

| NAME and Surname of each Person | RELATION to Head of Family | CONDITION | AGE | Rank, Profession, or OCCUPATION | WHERE BORN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Henry Webb | Head | Married | 36 | Labourer on the iron works | Wilts, Heywood |

| Jane Webb | Wife | Married | 26 | Wilts, North Bradley | |

| Arthur Webb | Son | 7 | Wilts, North Bradley | ||

| Edward Webb | Son | 5 | Wilts, North Bradley | ||

| Gideon Webb | Son | 3 | Wilts, North Bradley | ||

| Jane Butcher | Servant | 13 | Domestic servant | Wilts, North Bradley |

When I discovered that Jane Webb in 1871 was the same Jane as the one described above, I looked for her son Fred on The Rank, but found no sign of him.

In fact, he is in nearby Trowbridge, living on Mortimer Street. He’s 10 years old, and living with Jane’s father’s family (who had been living on The Rank in 1851 and 1861).

| NAME and Surname of each Person | RELATION to Head of Family | CONDITION | AGE | Rank, Profession, or OCCUPATION | WHERE BORN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Henry Bennett | Head | Married | 49 | Smith | Trowbridge, Wiltshire |

| Eliza Bennett | Wife | Married | 48 | Trowbridge, Wiltshire | |

| John Bennett | Son | Unmarried | 24 | General servant | Trowbridge, Wiltshire |

| Tom Bennett | Son | Unmarried | 21 | Cloth worker | Trowbridge, Wiltshire |

| Frederick Bennett | Grandson | 10 | Scholar | Trowbridge, Wiltshire |

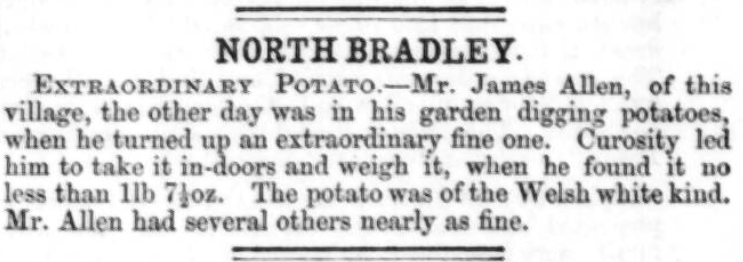

There were clearly some big changes for Jane and Fred in the decade between 1861 and 1871. I found Fred’s baptism record from 1863 – he was baptised in North Bradley on 2nd August, when he was 3 years old. There is no name given for his father, and Jane’s occupation is given as ‘Weaver’.

Jane married Henry Webb on 19th September 1863 (the month after Fred’s baptism), in North Bradley. Three children quickly followed, who appear on the 1871 census at The Rank (see above).

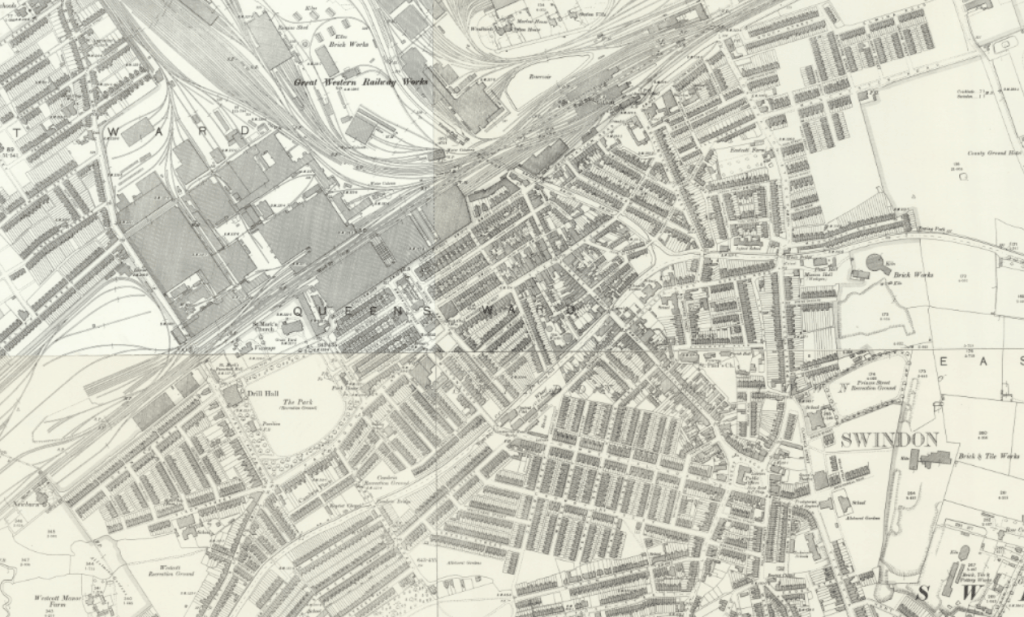

After Fred grew up through his adolescent years between 1871 and 1881, at some point he moved to Swindon – a fair distance from North Bradley and Trowbridge, 28 miles and 38 chains by rail. And it was the railway that took Fred to Swindon to work, as an engine/fireman. In 1881, when he is 20 years old, he is living in Swindon with Job and Emily Hunt, on Albion Street.

| NAME and Surname of each Person | RELATION to Head of Family | CONDITION as to Marriage | AGE last Birthday | Rank, Profession, or OCCUPATION | WHERE BORN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job Hunt | Head | Married | 27 | Boiler Smith | Stratton St. Margaret, Wiltshire |

| Emily Hunt | Wife | Married | 30 | Lambourn, Berkshire | |

| Frederick Bennett | Lodger | Unmarried | 20 | Fireman | North Bradley, Wiltshire |

The 1881 census was taken on 3rd April 1881, and – utterly tragically – it was taken a little over 6 weeks before Fred died.

The first record I found of Fred’s death was a burial record in North Bradley, on 23rd May. I quickly realised he was only 21 when he died, and felt immediately sad, because I’d already become quite attached to this character, wanted to know more about where he went and what he did with his life.

However, when I searched his name on the British Newspaper Archive, I discovered the circumstances of his death in the very first result.

Reader discretion is advised for the following extracts. As a general rule, we shouldn’t look to 19th-century newspapers for either sensitivity or tact when it comes to reporting tragic fatal accidents, and the descriptions below are incredibly graphic.

The first article is from the Trowbridge Chronicle on Saturday 21 May, when news of the accident had only just begun to filter through from Swindon.

NORTH BRADLEY

ACCIDENT – At 5 o’clock on Wednesday evening, a young man named Frederick Bennett, a native of Bradley, who is in the employ of the Great Western Railway Co., at Swindon, met with a serious accident, injuring his ribs. Bennett is an engine driver, and it appears he was either crushed or knocked off his engine. He is in a very precarious state.

‘A very precarious state’ is only a tiny glimmer of hope, but things aren’t sounding good.

The next article is from the Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, a week later on Saturday 28 May, and our worst fears are realised.

NORTH BRADLEY

FATAL ACCIDENT – On Wednesday in last week a young man named Frederick Bennett, employed as a cleaner in the narrow gauge engine shed [Gloucester branch] at Swindon station, met with a frightful accident. It appears that he was riding on the foot-step of a locomotive, and being engaged in conversation neglected to get on to the foot-place on approaching the entrance of the shed, where there is only about five inches clearance between an engine and the pier. Bennett was crushed into this space and literally rolled round. He was immediately conveyed to the Hospital [Great Western Railway Medical Fund Accident Hospital]. Several of his ribs were contused, besides which he sustained severe injuries to his head and body. Every attention was paid to him, but the shock to the system and the physical injuries were so severe that the unfortunate man died on Friday morning at ten o’clock. An inquest was held on the body on Saturday by Mr. Coroner Baker, and a verdict returned of “Accidental death.”

Mr. Coroner Baker’s findings are reported in the Devizes and Wilts Advertiser on Thursday 26 May 1881.

INQUESTS BEFORE MR. CORONER BAKER

On the 21st inst., at New Swindon, on the body of Frederick Bennett, of 10 Auburn Terrace, New Swindon, aged 20 years, an engine cleaner on the G.W.R. It appeared that on the 18th inst, about 2p.m., an engine was coming out of the engine shed at Swindon station, when the fireman on the engine heard something rub against the engine shed wall, and upon looking round saw the deceased between the engine tank and the wall. The engine, which at the time was going very slow, was immediately stopped, but the deceased was crushed so badly that he died from the effects on Friday the 20th inst. Neither engine driver or fireman saw the deceased before the accident, and it is supposed that the deceased must have jumped on the step of the engine to ride out of the shed, and so received his injuries. The jury returned a verdict of accidental death.

The extent of Fred’s injuries, and the time between the accident and his ultimate death are utterly beyond imagining, and it’s heartbreaking to read it in such formal detail. Sadly, injuries and deaths on the railway were not uncommon, and Fred’s story is unfortunately not an isolated one. In 1900 alone, over 16,000 railway workers were injured or killed1, and it wasn’t until 1913 when the management of the Great Western Railway introduced the Safety Movement, designed to educate their employees on working safely.

Besides the horror of Fred’s death, there is one very touching detail at the end of the article from the Wiltshire Times on 28 May 1881, that gives us a sense of what Fred was like as a man and a workmate.

The remains of the deceased were conveyed to Trowbridge by train, on Monday morning, and afterwards interred in the churchyard at North Bradley, of which place he was a native. Several of his fellow workmen followed the body to its resting place, out of respect for the deceased.

That several of his colleagues chose to accompany Fred on his final journey back home to North Bradley must speak volumes of his character. The fact he was killed so young remains tragic, but a detail like this is heartening, and shines a small light of humanity on just one of the many tens of thousands of railway workers’ deaths over the past 200 years.

Postscript – While researching this post, and entirely separately from looking into the story of Fred Bennett, I came across the incredible work of the Railway Work, Life & Death project, which uncovers the stories of accidents and deaths on the railways in Britain and Ireland from the late 1880s to 1939. Please do go and look at their work, and read some of the incredible stories that the records can tell, thanks to the efforts of the organisations involved and a team of volunteer transcribers. A downloadable archive of their findings is available for free, providing a wealth of information.

References

1 https://www.railwaymuseum.org.uk/objects-and-stories/caution-railway-safety-1913

Leave a comment