One of the things I was really keen to do when starting this project was match the residents enumerated on every census from 1841 to 1921 (plus the 1939 register) with the houses they were actually occupying.

On the face of it, this seemed a fairly reasonable, sensible, and straightforward thing to do. It would help me to place people in space, and time, and track the houses through subsequent changes of hands.

I chose to use the census records because that’s simply the easiest source I had to hand. Even without ready access to historic Land Registry records, I thought that it wouldn’t be too much of a problem to assume that each enumerator took a relatively straightforward and direct path down The Rank, and that each house would be represented in that order on the census return itself.

Oh, how wrong I was.

I can chalk it up to experience now, but I should have realised sooner that this was, in fact, no simple task.

The main factor in its complexity was that The Rank is not so much a street as a collection of groups of cottages. Mercifully, some of them are in rows, but even then, the rows are jumbled among themselves, with standalone cottages dotted in between. It quickly became clear that the enumerator’s route was always a casual, leisurely ramble, collecting names as they went, and going back to pick up households missed and putting them in later down the list.

To help me work around this, I had a handful of relatively reliable assumptions that I could base my working on:

- Despite the clustering of cottages, the lane is linear, with Axe & Cleaver Lane at one end, and Southwick Road at the other

- Some buildings are larger than others (and can therefore house larger families)

- Some buildings show definite evidence today of having been combined, or split, over time

The first point in particular made it easy to orientate myself depending on whether households on Axe & Cleaver Lane came before or after The Rank. If before, then the houses at the north-west end are covered first; if after, then the houses at the south-east end should come first.

I was also aware that one family – headed by Arthur Culverhouse – always appeared at the top or bottom of the census every time they were represented, and, knowing that they lived at what is now No. 1, this helped to confirm the orientation of the schedule list (or the beginning of it, at least).

Another key piece of information was knowing that Edward Culverhouse – my great-great-grandfather – lived at what is now No. 8 in 1911 and 1921. This would prove crucial later on…!

With the raw data ready, and armed with these key facts, I could begin to put the pieces together.

Step One: Listing Families

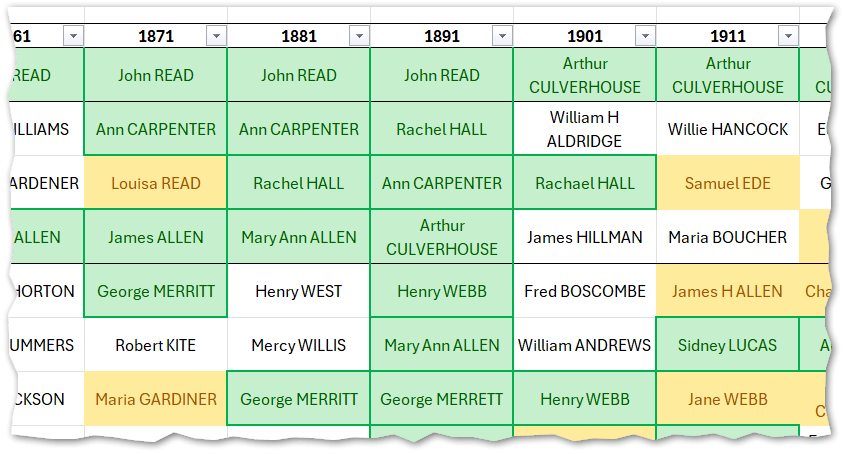

My first approach was to list out all the family names in a single table, in the order that they were enumerated, in each decade, side by side. I colour-coded the names to indicate whether the same person listed as the head of the household appeared on consecutive census returns (in green), and also whether the same family name appeared more than once (in yellow), which could suggest children inheriting from parents.

Two things became apparent very quickly:

- The order of households on the census bore only a passing resemblance to the actual position of the houses on The Rank

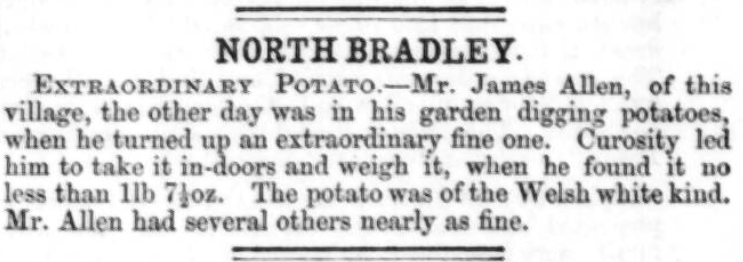

- There were a lot of repeated family names – in addition to the snippet above, the whole list of between twenty-nine and thirty-two households was almost completely green or yellow, and uncoloured cells were in the minority.

I tried my best to adjust the positions of names to align them with the instances where the same families stayed put, but moving one name just created problems with names elsewhere, where I didn’t have enough information to confidently place them in a different spot.

What also presented a challenge was not knowing which schedule number related to which house. Combined with not able to rely the houses being listed in a particular order, I realised I needed to take a different approach.

Step 2: Listing and comparing buildings ‘now’ versus ‘then’

My next step was to look at OS maps from the 1880s and compare them to a modern map to work out the capacity of The Rank in the past, and where the residents could realistically have lived, or where they might have moved, if they moved but didn’t leave The Rank.

This was the point where I began to put houses into groups, and assuming that the enumerator would realistically have gone to those houses next door to each other.

Again, this was an imperfect strategy, but the assumption did prove to be reasonably sound – there were clusters of names that tended to appear near to each other in the census, and my working theory was that this would align with those groups of buildings.

The groups, moving east to west, were as follows:

- The large house at the top of The Rank, the bakery/shop, and the cottages adjoining it (what are now Nos. 1, 2, 2a, and 3)

- The roughly east-west row of cottages next to the first group (modern Nos. 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8)

- The large house surrounded by a large plot (now No. 9, with No. 8a behind it and No. 9a nearby, both built after 1939)

- The long, roughly north-south row of cottages a short distance from No. 9 (modern Nos. 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, and 15 – nearby No. 16 was built after 1939)

- The pair of cottages next to the row above (modern Nos. 17 and 18)

- The large detached house and the group of houses across the road (now Nos. 19, 20 & 22)

- A large cottage set back from the road, and the two cottages next to it (modern Nos. 23, 24 and 25)

- Now demolished, there were also two large houses with extensive plots that became known as Rank Farm

- Finally, a small row of cottages, set far back from the lane, that also no longer exist.

This was a help when roughly aligning names to a vague area of The Rank, but it still didn’t give me the surety I wanted in order to feel like I’d properly cracked it.

I desperately needed something else if I wanted to do this with the records I had available directly online. By chance, I remembered one more source that I’d seen while casually browsing a while ago, and I looked into it again to see if it would help.

Step 3: The Wiltshire Tithe Award Register 1813-1882

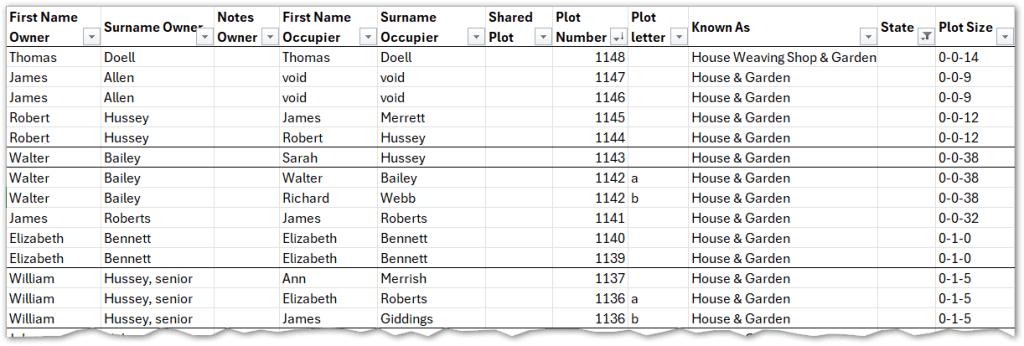

The Wiltshire Tithe Award Register was transcribed by the Wiltshire Family History Society.

Searching for just one of the names from the 1841 census gave me that elusive ‘eureka’ moment. Suddenly, I had a way of assigning a plot number to a family, since I now had the name of the owner, and – most importantly – the name of the occupier.

Because the records for The Rank were from 1846, I could match some of the names on the tithe award register to where they appeared on the 1841 census. I finally felt I had a a starting point for tracing the residents through subsequent decades, since, as I’d already seen, some families did stick around for more than ten years.

I collected the data for the plots on The Rank based on the names I had on the census, and a partial picture of The Rank’s buildings in the mid-19th century began to emerge. However, I was still missing the rest of the plots because not all the names I had for 1841 were on the 1846 record, and without any way of searching for the plot number on Find My Past, I was left with gaps. I considered it to be a good start, at least, and a phenomenally useful addition to the data I had been gathering for the entire study.

Just before I dived headfirst into another round of matching efforts, I made one last-ditch attempt to find an old parish map of North Bradley online, in case it happened to refer to the old tithe plot numbers. With a little perseverance, I stumbled across the final piece of the puzzle.

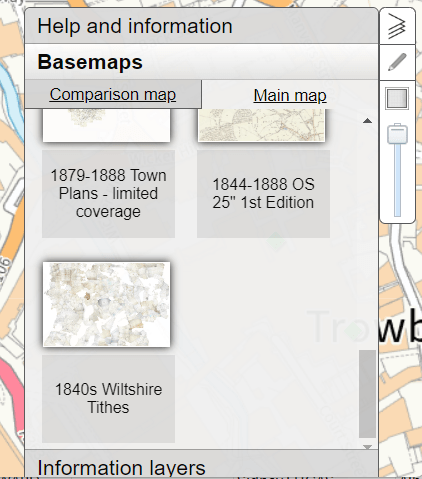

Step 4: KnowYourPlace – 1840s Wiltshire Tithes

On the Bristol City Council website, among the options on the KnowYourPlace site, the ‘Basemaps’ option is hiding, tucked away at the top. I clicked on it, and hesitantly scanned down the list of maps available to choose from.

Right at the bottom, there it was: 1840s Wiltshire Tithes.

I am ashamed to admit I was genuinely holding my breath as I clicked on it and panned across from Bristol to North Bradley. I zoomed in and there they were. All the plot numbers, some of them smudged, but mercifully still legible.

Dear reader, I squealed with joy. This is what a One-Place Study does to you.

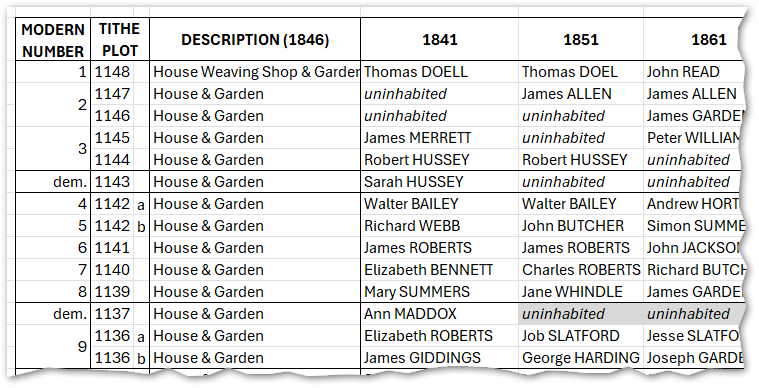

I went back to my extract of the Wiltshire Tithe Award Register and filled in the missing plots. Finally, there it was, a full list of every building on The Rank in 1846, and the name of each occupant at the time.

Armed with this list, a matching map, and each census from 1841 to 1921, and the 1939 Register, I could get to work.

Step 5: The Final List

To begin with, I worked one step back, comparing the 1841 census line by line. I mentioned before that there were gaps in the tithe list, and this was due to the 1841 occupants having left by the time the 1846 list was done. This was where some educated guesswork came into play (the same guesswork that I’d need to use for later decades as those names changed as well).

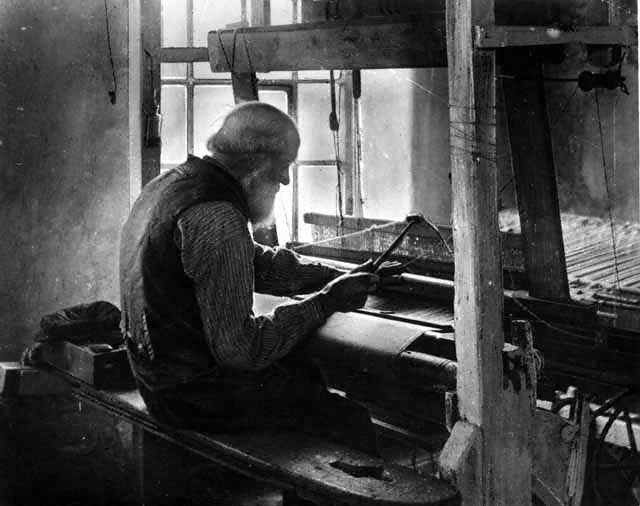

The main assumption I had to work with was the number of people in each household, and the relative size of the plot, including any land being worked on (which helped distinguish a household headed by an agricultural labourer versus a weaver, for example). I won’t go into detail here on the main threads of logic I followed; the magic of what the contents of the list can tell us deserves a whole other post all on its own.

Slowly but surely, I was able to piece together nearly 100 years of residents, taking my list from the early jumbled attempt that looked like this…

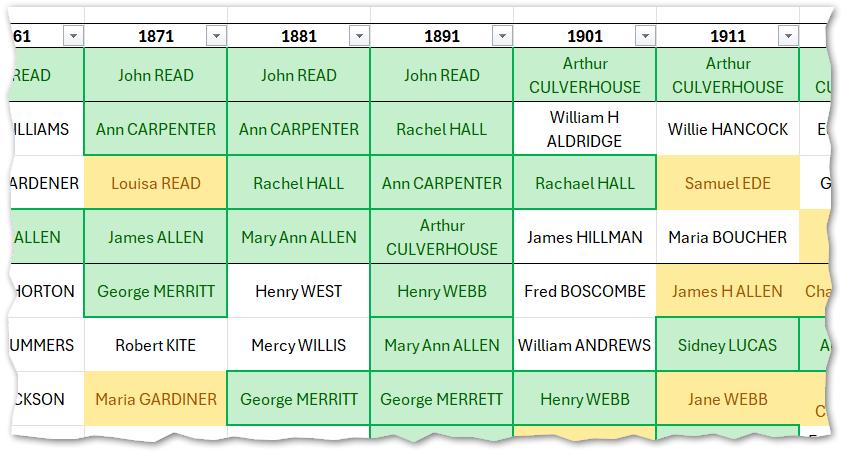

…into something that suddenly made a lot more sense, and just ‘felt’ more right:

All households are covered, all the way up to 1939, with several families – well-known North Bradley dynasties – stretching across many decades.

I have no doubt that there are mistakes and faults in the logic, and I am certain I will unearth more evidence that will help me correct them. But in terms of providing a foundation for telling the story of The Rank and its people, it’s an incredible milestone in putting together this One-Place Study.

I’ll write more about the specific challenges I came across during this exercise, and dive into some of the detail that paints a picture of the changing face of The Rank over time (such as pinpointing the demolition of buildings, or when two houses combined into one, or when one was split into two).

But as a start, it certainly feels like a good one.

Leave a comment